The Trolley Problem & Ethical Dilemmas: How Do We Decide Who’s Good and Bad

Crime fiction is full of ethical dilemmas and morally grey characters. They help us make sense of how ordinary people can be driven to do bad things, but they also help us understand ourselves. With that in mind, I want to ask you a question:

Would you kill one person to save multiple others?

This is the premise of the famous moral dilemma, the trolley problem.If you’ve not heard of the trolley problem before, it’s a hypothetical scenario where a trolley is racing out of control, on its way to squish five people tied to the track (unlike a good crime novel, we never find out who did this). But by pulling a lever, you are able to divert the trolley onto a different track where only one person is tied. You can save five by killing one. Do you pull the lever?

90% of us make the decision to pull the lever. We can justify this with utilitarian ethics— killing one person to save the five is the most ethical option because it produces the greatest good for the greatest number of people. But let’s complicate this scenario. What if the one person is your best friend? What if the five are all terrible people?

In my debut novel, An Ethical Guide to Murder, this is the situation Thea finds herself in. She discovers that she has a power—she can tell how long people have to live. Not only that, but she can take life from one person and give it to another. She first uses this power—without fully understanding what she’s doing—to save her best friend, killing someone else in the process. Then she’s left wondering: if she can save good people by killing bad ones, shouldn’t she do it?

Thea takes a utilitarian approach, creating “The Ethical Guide to Murder” to help her use her power for the greater good. But of course, it’s much harder to identify the most ethical decision when we can’t reduce the options to numbers. How do you decide which lives have more value than others? How do you know if someone is truly good or bad? If someone has committed a crime, do they not deserve a chance at redemption?

In addition to this ethical minefield, Thea’s not exactly the person you’d want to have this power. She’s an impulsive twenty-six-year-old with a traumatic past who struggles to be responsible for her own laundry. Despite this, she wants to be a good person and do the right thing. This was one of my favourite themes to explore in the novel—how does someone commit murder and still convince themselves that they’re a good person? In psychology, this kind of contradiction is referred to as cognitive dissonance. It feels uncomfortable, and we want to find a solution, which is another reason Thea created her new ethical framework. Not just so she can do good, but so she can feel good too.

At the start of the book, Thea is—at best—an average person. Yet this is not how she sees herself. I wanted to give the power to a character like her because this is true of all of us to some extent. We’re very good at cherry picking things that confirm our beliefs and discounting things that contradict them. For example, we all tend to think we’re slightly better than other people—even convicted criminals believe themselves to be more moral than law-abiding citizens. This is important because our belief in our ability to make moral decisions has very real consequences. Judges give out harsher prison sentences before lunch because they are tired and hungry. This just makes them human, and none of us are aware of the huge number of factors influencing our decisions and behaviour on a daily basis.

Clearly, Thea’s actions are far more extreme. But if you’re intrigued and decide to pick up a copy, I’d like you to keep this in mind.

And as you’re reading, I hope you continually ask yourself, “What would I do?”

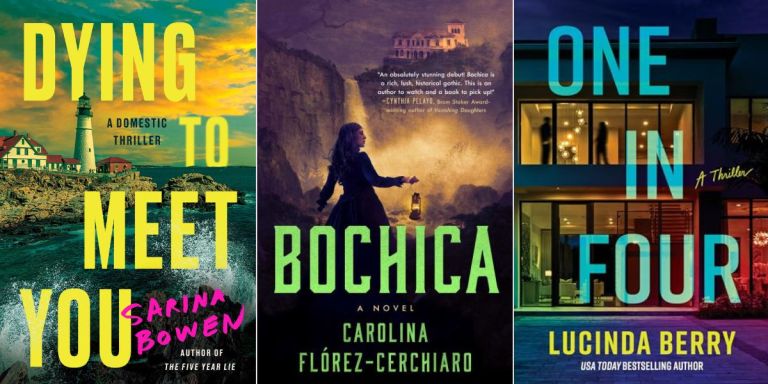

Discover the Book

Thea comes to understand that she has a godlike power, but how to use it quickly becomes a question of self-control. Is it really so wrong to take a little life from a bad person–say, a very annoying boss–and gift it to someone who’s truly good? Realizing she needs to harness her newfound skills, Thea creates an Ethical Guide to Murder. But as she embarks on her mission to punish the wicked and give the deserving more time, she finds good and bad aren’t as simple as she first thought.

How can she really know who deserves to live and die, and can she figure out her own rules before Ruth’s borrowed time runs out?

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use